[ad_1]

Belinda Joslin has owned, raced, maintained and repaired boats her entire life. So, when he looked for work after his children started school, he went to his bus station in Ipswich. They gave him a job to complete and quickly took the life out of him by sanding, painting and painting. “I got to the school gate and it was really dirty,” Joslin, 48, said.

Wanting to find other women who share her passion, she set up an Instagram account in May 2021 called Women in Boatbuilding. “I thought I couldn’t be the only woman in the world interested in fixing boats,” she said. “I wanted to connect with other women and listen to their stories. I have found some amazing, inspiring women.

In the beginning it was to celebrate each other’s achievements but as the women opened up about their experiences, they began to share some of their struggles and struggles. Boat building is still mostly done by men. Most of the women have experienced sex and find that they have to work harder than men to prove their skills.

“As an industry, we are far from gender equality,” Joslin said. “There’s so much more that can be done.” Joslin wants the account to be a force for advocacy for equality and diversity in boatbuilding, and a place to showcase and support women in the industry.

Sacha Walker

‘You are producing your share of beautiful sculpture’

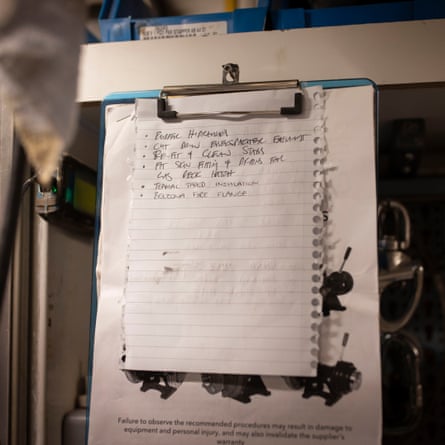

The hum and hum of the car park reminds Sacha Walker of the rhythms of a festival or gig. Walker, 53, a former tour operator and music salesman, now works as a finisher, sander and refinisher of custom-built boats at Spirit Yachts in Ipswich.

“We are working as a team, with one purpose. All that noise, all that energy flowed right through me. I feed on it,” he said.

After leaving London five years ago, Walker moved to Ipswich and began his photography career. In 2017, he visited Spirit to take pictures of people at work, and immediately felt at home: “I fell in love with the wind and the boats.”

When Spirit’s manager, Karen Underwood, offered Walker an opportunity to train to complete it, she took it. “I love you. There is no desk or email,” says Walker. “I was still moving and hit wood. I ended up hugging the boat like a whale’s back. It’s very physical.

“It’s very pure, artistic and creative,” he says. “You are producing your share of beautiful sculpture.”

About a third of Spirit’s staff are women but not all boats are equally inclusive or supportive, Walker said. In other places, “women are not treated well and have to prove themselves”.

Even if the genders are equal, he says, it will be more difficult for women – tools and work clothes are made for men: “It needs to be changed but not because it is useless or weak. “

Belinda Cree

‘People talk to you like you’re a fan’

Friends and family describe Belinda Cree’s work as a “painter and a misogynist”. He worked diligently to prepare the planks and finish of the boat, and, armed with a machine gun, hammered the blocks out of the hull.

“Boat maintenance is my specialty,” he says. “Right now I’m getting rid of the rust, which affects the rough parts of the steel fenders.”

Cree, 28, is a boat builder who repairs and maintains boats on land and at sea. He is currently working on the restoration of a 1962 30 meter luxury motor yacht as a contractor for a boat owner in Southampton.

He did not see himself going to sea. Growing up in Northern Ireland, a back injury as a teenager prevented his planned career in the military. It took years to learn how to live with his chronic pain and to be able to start a physically demanding routine.

Three years ago he took an apprenticeship with the National Historic Landmarks, a boat building course. “To live a good life, I have to put a lot of work into my life,” he says, “but it’s better to have like that effort in a job that I really like.”

As a woman in the maritime industry, she is still trying to prove herself. “I want to see how people who can work in this industry change,” he said. “People will talk to you as if you are a fan. There is very little space to not be very good in the yard: ‘You will allow me to be new or to learn, or you will think not Am I good because I’m a woman?’

He believes that groups on social media can help. “Seeing other women doing their own thing, especially women who are ahead of me, has more experience and is inspiring. It gives you something to aim for.

Obioma Oji

‘Physical strength is not the issue, it’s about solving problems’

Being close to the water is important, says Obioma Oji, a newly qualified boat builder.

Oji, 43, and three fellow graduates from the Lyme Regis Boatbuilding Academy have launched a start-up to build high-end and affordable wooden boats, sought after for quality, craftsmanship and sustainability, he said. his.

-

Oji tied up Ibis, a boat he helped build, at Lyme Regis; and identify wood defects in the university workshop

Oji was working as an interior designer at Ikea when the pandemic forced him to take a break from work and start a boat building course. She saw it as an opportunity to learn more practical skills and fuel her creative drive – before her career she worked in ceramics and interior design.

He started the course thinking he would like to sail or sail, “but I really liked woodworking”, he says. “Each tree is different and can’t be resisted, you have to push it, read it. Physical fitness is not an issue – it is a problem solver.”

There are few women in the course, as they are in the boat building industry. “We’re from outside,” says Oji.

Gail McGarva

‘The shape of the boat shows you its past, its work, its coast.

Gail McGarva isn’t usually thinking when she’s building her vintage work boats in her Lyme Regis workshop. Finding a missing boat, he made a model called a “daughter” boat, following the lines of the mother boat, building it by eye.

“I was drawn to boating,” he said. “They work hard. Each boat is strong, beautiful, and has a story to tell. You look at the shape of the boat, and it tells you about its past, its work, its coast.

After spending years on a boat, McGarva, 57, decided to pursue careers in theater and as a translator. He trained in boat building 18 years ago and is passionate about preserving heritage.

His work included the construction of 32ft (9.75-metre) Cornish pilot boats, which were revived in the 1980s by master boat builder Ralph Bird. Racing them is now a popular sport.

“Usually as traditional boat builders, we focus on restoration, but I’ve been lucky enough to get a lot of interest in gigs, and clubs asking for new boats,” he says. “It was an honor to have Ralph Bird as my mentor – it’s important to have someone say you can do it.”

McGarva has received numerous awards, including the British Empire Medal for services to boatbuilding and heritage, McGarva runs workshops around the country, talks about the sector of these boats to our heritage.

“It was always a male reserve,” he says, “but I always believed that anything was possible. We need more role models for women.”

[ad_2]

Source link