[ad_1]

HALIFAX, NS –

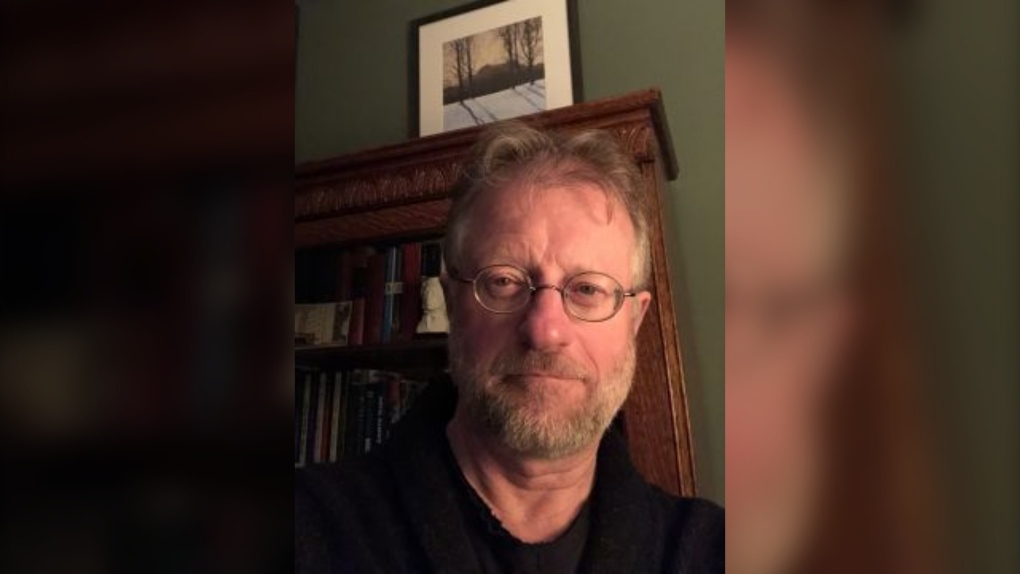

A Canadian ecologist and fisheries scientist who criticized political interference in scientific advice on declining fish populations — particularly northern cod — has died at age 63.

Colleagues in Dalhousie University’s biology department said Jeffrey Hutchings, a longtime professor at the Halifax school, died at his home over the weekend. The cause of death was not released.

John Reynolds, chair of the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada, was a lifelong colleague and described Hutchings as an intellectual soulmate who believed passionately in the value of ensuring that public policy decisions they could be guided by unbiased science.

Hutchings was the chair of the same committee from 2006 to 2010, leading a team of about 40 scientists in assessing which Canadian species were at risk of extinction.

Reynolds, a professor at Simon Fraser University, remembered Hutchings as a principled man who used his background in ecology and evolutionary science to understand fisheries and to demand more independence from scientific advisers to decision-makers. federal

“It went against the grain in terms of how fisheries scientists thought about stocks,” Reynolds said. “He looked at the organism, the fish itself, and said, ‘Wait a minute, this species of fish is going to take many years to reach maturity, so it’s going to take many, many years for the fish population to rebuild. “. “

“These kinds of things seem obvious, but they are lost,” he added.

Hutchings was not shy about calling out scientists and former civil servants for the mismanagement of Northern cod species in the 1990s. “He was fresh out of graduate school and looked at the data as it was happened … and he said, ‘It was overfishing that did it, pure and simple,'” Reynolds recalled.

He said some in the federal Department of Fisheries tried to push the collapse as a result of a mix of ecological factors rather than overfishing.

In 1997, Hutchings and two co-authors wrote a clear article for the Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences questioning whether government-run science could be trusted to provide independent advice to decision-makers. The paper’s abstract noted how “non-scientific influences may interfere with the dissemination of scientific information and the conduct of science in the Canadian Department of Fisheries and Oceans.”

The cod fishery off southeastern Labrador and northeastern Newfoundland, once the largest on the planet, was closed on July 2, 1992 after a massive decline in the cod population, which resulted in the loss of approximately 30,000 to 40,000 jobs.

Hutchings’ frank diagnosis several years later of the failure of the federal Department of Fisheries to clearly state that overfishing was the cause, “led to an enormous amount of attention and backlash against him from officials and some science,” Reynolds said.

In 1997, a release of the government invective to the media referred to the newspaper article as “science fiction”, written by professors who used innuendo and misrepresentation.

However, Hutchings did not move away from his position that science needed to be more independent, while he also praised governments if they added scientific staff. During the government of former prime minister Stephen Harper, Hutchings continued to request science arms to provide advice on the state of fish stocks. In 2016, he praised the federal liberals for the reconstruction of the scientific staff in the federal Department of Fisheries.

Aaron MacNeil, a former student who became a colleague at Dalhousie University, said that his mentor will be remembered for defending “the primacy of science in decision-making”, as well as the obligation of scientists to tell the truth once they have discovered it. .

“I knew that science can help make better decisions and that can have a major influence on people’s lives and lives,” he said.

This report from The Canadian Press was first published on February 1, 2022

[ad_2]

Source link